Topics

Learn more about

the Book Topics

Chances are that at least one of these things is familiar to you, whether you’re a parent who has looked at the schooling options for your child(ren), or you’ve seen one or another of these labels on products at your local health food store (or in your chain store’s new “healthy choices” section). Or maybe you’ve seen them as a student of comparative religion, or even of some of the so-called “alternative religions” that seem to be growing in popularity and/or public awareness. What you may not know is that a single thread runs through all of these diverse practises, and others that may seem even more disparate as well

THe STeiner Movement

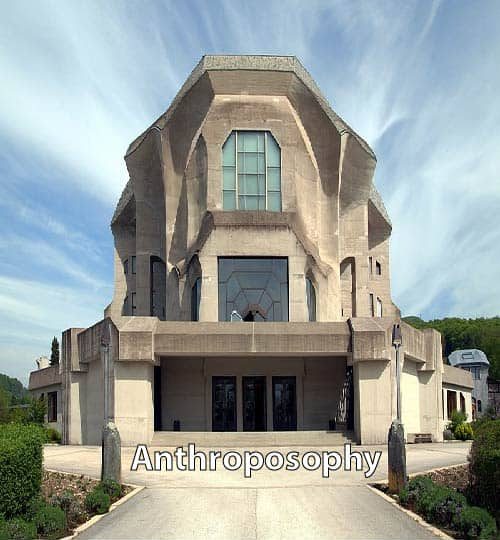

That thread is Rudolf Steiner — whose dedication to sharing his ‘spiritual science’ with the world led him to found what has become a world-wide movement based upon his teachings.

This has been difficult for outsiders to this movement to fully perceive and understand, because to know Rudolf Steiner in the context of only one of the institutions he founded is to know only a facet of his background, or his teachings. Those who know of him only as the founder of the Waldorf schools, for instance, conceive of him as an educationalist — they are generally seeking to know only his background in this area, and this is what is presented to them when they inquire about the founder of this “alternative, arts-oriented” form of education.

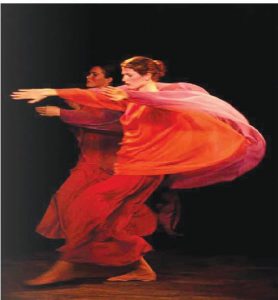

Yet his schools derive as much or more from his other aspects as from his background as a tutor, and the years he spent in his twenties, educating the children of the Specht family. Much of his dedication in those years is shown in the arduous care he devoted to the ‘sleeping soul’ of one of the boys, who overcame his ‘water on the brain’ to become a doctor. It is from this experience that he derived many of his beliefs about the potential of ‘curative education’, which in turn take form in the practise of Eurythmy, and in more specialised form in the Camphill Communities for the disabled, where staff and patients live together as ‘co-workers’ and ‘villagers’, with no social dividing line between them. Developed still further, these teachings became the field of Anthroposophical medicine, whose leading brand name of Weleda is now a common sight in health food and natural products stores the world over.

Likewise, many ‘green’ consumers, in shopping for organic foods, have gotten used to seeing biodynamics as just another word for ‘organically grown’, or at best a certain set of organic production standards. Yet, like the Waldorf schools, the entire practise of biodynamic agriculture has a much deeper set of beliefs and practises behind it, far beyond its avoidance of synthetic chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides. These too are sourced from Steiner’s unifying ‘spiritual science’, in addition to the invaluable bits of pre-industrial agricultural knowledge that he gathered from the farmers of the rural countryside, and preserved through the height of the Western world’s infatuation with the new wonder sprays of chemical agriculture.

Steiner as the common thread

It is Steiner’s role as self-proclaimed clairvoyant and founder of the modern mystery movement of Anthroposophy which begins to shed light on this unifying thread. However, prior to Geoffrey Ahern’s doctoral thesis, which he developed into this unique and ground-breaking book on Steiner, on his teachings, and on the historical and religious background in which they arose, there was no cohesive source to which an interested reader could turn to in an effort to answer these questions.

Steiner himself wrote and spoke at length on his teachings — but the very abundance of his own writing makes it hard for an outsider to even begin to understand the scope of the material he covered. In addition, much of what he taught required the development of specialised language, to describe the concepts he sought to explain; between these factors, and his now-outdated writing style, it is little wonder that the newcomer to Steiner is often told “Steiner is difficult” when they turn to his own writings in an effort to understand the institutions that he founded, and find themselves more confused after their reading than before they began.

Others have written about him, but it doesn’t take long to see that these writings quickly fall into two easily-distinguished camps — proponents of Steiner and his teachings, and detractors.

Only in Sun at Midnight, the compassionate and carefully impartial sociological exploration of the institutions and their founder has found a neutral and unbiased expression. This book offers, in one volume, a comprehensive, cohesive, and coherent outline and description of Steiner’s own life, his teachings, the institutions founded upon those teachings, and the multi-millenia-long Western esoteric tradition from which Steiner (and so many others) arose.